My life became more full fat with miracles the day honeybees flew into my heart and onto our land here in Appalachia. One of the early epic moments I experienced with them was in April of my first spring with-bee, when something happened that no one had ever told me about.

Joe and I had gone out to enjoy the music of one of our most favorite artists in the world, Omar Faruk Tekbilek, a wonderful Turkish musician, singer and composer whose work is profoundly devotional and inspiring. We came home from that concert with our hearts blown wide open. It was late. Joe went to bed, but I couldn’t sleep so I went to the bee sanctuary. Night-time in the bee yard is magical; it is governed by starlight and the moon, and not the light of the day sun. The symphony of sounds that emerge from the hives, and from the choir of creatures around them, is its own sacred soundscape.

Joe and I had gone out to enjoy the music of one of our most favorite artists in the world, Omar Faruk Tekbilek, a wonderful Turkish musician, singer and composer whose work is profoundly devotional and inspiring. We came home from that concert with our hearts blown wide open. It was late. Joe went to bed, but I couldn’t sleep so I went to the bee sanctuary. Night-time in the bee yard is magical; it is governed by starlight and the moon, and not the light of the day sun. The symphony of sounds that emerge from the hives, and from the choir of creatures around them, is its own sacred soundscape.

I was about to begin my evening ritual of putting my ear to each hive to say goodnight and tell them how much I loved them. As I started to incline my head towards the side of one hive, the moon suddenly emerged from behind the ridgeline and crested the trees. All of a sudden the whole bee yard and everything within sight … the trees, the hives, my skin, the ground … was bathed in silver blue light. I had forgotten there was a full moon. At that same moment, I completed the arc of putting my ear to the hive beside me and heard the most extraordinary cries coming from the heart of that colony … like the haunting call of seals or birds on a distant beach. Nothing was wrong; nothing was frightening. I felt like I had fallen down a rabbit hole into some kind of otherworldly, moonlit bee dream.

Here is a recording of this same song from another hive, a few years later. It lasts about a minute:

Isn’t that astonishing? You can hear tooting and also some quacking, but it is the piping, those long sustained higher notes that mesmerized me. I phoned my friend Carl first thing the following morning and he said I had heard queen piping, a call sometimes made by virgin queen bees, most often before they are born.

The week before, I had counted eight peanut-shaped queen cells (the birth chambers) in that hive. It takes 15 – 16 days for a queen to be born, to change from an egg to a larva to a pupa and then eventually emerge from her cell as a young adult. She hatches from the bottom of her cell and generally, the first queen born gathers herself, travels to the other queen cells (the ones not yet quite born) and kills those other contenders by stinging them through the wax walls of their birth cells … because only one queen will reign in a hive.

The week before, I had counted eight peanut-shaped queen cells (the birth chambers) in that hive. It takes 15 – 16 days for a queen to be born, to change from an egg to a larva to a pupa and then eventually emerge from her cell as a young adult. She hatches from the bottom of her cell and generally, the first queen born gathers herself, travels to the other queen cells (the ones not yet quite born) and kills those other contenders by stinging them through the wax walls of their birth cells … because only one queen will reign in a hive.

Michael Bush, who is a natural beekeeper I appreciate, describes how a virgin queen pipes: she coordinates her breathing, the buzzing of her wings and the vibration of her body, which she places in contact with the comb inside her birth cell. The resulting piping resonates like a sort of sounding board in the hive, passing the vibrations along the comb to the bees.

Some of the prevailing mainstream thinking about this phenomenon is that it has to do with rivalry. Some call it a form of battle cry between competing soon-to-be born queens who are assessing each other’s fighting abilities. Alan Chadwick, the legendary horticulturist and visionary, called it a Valkyrian cry, a sound that pierces the veil. And there are other theories, but this is still a territory of great mystery and, to me, is one of the hallowed songs in bee life. I have heard it many times over the years and every time I do, I feel like I am in the presence of some kind of high church, holy-rolling Moment in a hive. I call this The Song of the Unborn Virgins.

Three of the primary ways that bees communicate with each other are through dances (inside and outside of the hive), the distribution of pheromones around the colony, and vibration. Bee life is a whole world of intelligent, purposeful vibration, felt by the bees’ legs and bodies through the resonating structure of wax on which they stand and in the air around them. Bees are immersed in and depend on a constant very complex and sophisticated exchange of vibratory signals.

When we think about hive health and a colony thriving, people often focus on things like the size of a population, the laying pattern of a queen, or how much nectar is being gathered and honey stored. But there is a whole other conversation that has always interested me which is the aural culture and health of a hive … the vibratory world and its relationship to the vitality and longevity of that colony and really, part of who that colony is.

Queen piping and other bee songs are full of intelligence, purpose and intent. They might range from winter cluster humming to the high-pitched keening of a queenless hive, rumbling forms of distress, the buzz of wings as workers come and go on a warm weathered day, the fanning of wings to maintain temperature and ripen nectar, the fuller bodied lower register and pitch of drones coming home in the afternoon … to queen piping. The bees are singing and they are vibrating the life of their colony into continued being.

My own experience of queen piping leans away from the battle cry thing. I am much more interested in the vibratory field that the queen’s call creates, which I experience as a kind of queen bee darshan (a Hindu word for a blessed transmission or transmission of blessings). I believe this sacred sound event, when it happens, is an essential part of maintaining a continuity, identity and integrity of essence in that particular lineage of bees.

There is a Sanskrit word, anahata, which means the un-struck, inaudible sound behind all of reality, from which reality is born. And the audible sound closest to anahata is considered to be the buzzing of bees. My friend Layne Redmond called it the celestial buzzing of creation. I also experience queen piping as an emanation from the heart of creation, like a sort of Aum but differently primal, feral and femininely mysterious … which is how I believe the feminine at its heart recognizes itself.

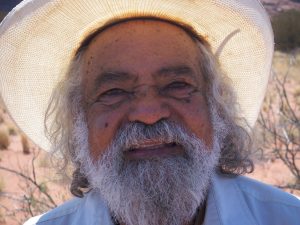

Queen piping also has resonance for me with the concept of songlines, which is something our friend Uncle Bob Randall used to talk about. Uncle Bob was a special teaching uncle and elder of the Yankunytjatjara Nation in Australia. He was one of the great people of our time and a living example of Kanyini, the Aboriginal principle of unconditional love, responsibility, and what he called Oneness with the creative consciousness of the world.

Queen piping also has resonance for me with the concept of songlines, which is something our friend Uncle Bob Randall used to talk about. Uncle Bob was a special teaching uncle and elder of the Yankunytjatjara Nation in Australia. He was one of the great people of our time and a living example of Kanyini, the Aboriginal principle of unconditional love, responsibility, and what he called Oneness with the creative consciousness of the world.

Uncle Bob told us a songline is a song of creation that energizes a belonging and connection with our place of creation, with everyone in that place who we are connected to (all of our family members that include all the beings, not just humans), and with the earth. He said that each child (or tree or bee or animal or any fellow family member) is born to a particular songline.

When he was a child, Uncle Bob said that his aunts and uncles would teach him a lesson that could go something like this: They might discover the tracks of a snake in the sand one morning and then learn everything about that snake family and its wider family. This would include Bob’s own human family that lived there, as well as with the hill beyond the snake’s tracks, the tree alongside the path they stood on, and the red rocks that were over the other way. You were family with everything there and the songlines were part of what bound you in a sacred way.

Over the years, when I hear queen piping, I think of Uncle Bob and what he had shared. Whatever the fullness of the queen’s call is really about, I also feel it is part of a colony’s songline. The queens, the one that will become the queen and all the other virgins whose lives may only last a few days more, are singing familial connection into being … announcing the imminent emergence of a queen and her essence into form, connecting the colony with that place on earth and with their other relations. In my bee sanctuary that would mean with the wasps, ants and lizards; the tulip poplar trees and white pines; the wild turkeys and black bears; the ridge to the north of the yard; the mountain the hives sit on … and with me.

There is some sacred something going on.

It is interesting to note that a queen bee can live three to five years. All the workers and drones, the great numbers of everybody else you see in a colony, only live about six weeks. So there is a big difference in lifespan between a queen and her fellow bees. Where I live in North Carolina, an Italian queen bee (which is the type of bee many of us have in America) can lay almost twenty generations of bees (from eggs to hatched) in the warm weather months of one year. So if you multiply those twenty generations of bees per year times the three to five years of a queen’s life, I imagine a songline that extends its reach to an immense number of bees and beings.

It is interesting to note that a queen bee can live three to five years. All the workers and drones, the great numbers of everybody else you see in a colony, only live about six weeks. So there is a big difference in lifespan between a queen and her fellow bees. Where I live in North Carolina, an Italian queen bee (which is the type of bee many of us have in America) can lay almost twenty generations of bees (from eggs to hatched) in the warm weather months of one year. So if you multiply those twenty generations of bees per year times the three to five years of a queen’s life, I imagine a songline that extends its reach to an immense number of bees and beings.

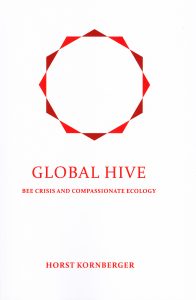

Several years ago, I talked about queens with Horst Kornberger who wrote a wonderful book called Global Hive: Bee Crisis and Compassionate Ecology. We are both concerned about the problems of requeening, which is a practice that modern beekeeping has come to embrace. The existing queen in a hive is killed (or dispatched) and replaced, most often with a virgin or newly mated queen who is often from an entirely different hive of bees (and often from commercial breeders). The new queen is added to a colony that was going along just fine with the queen they had from the bees’ point of view. Many beekeepers are strongly encouraged to requeen their hives every two years and now, even once a year, to ensure (I believe mistakenly) the health, vitality, and productivity of a hive. I am particularly disturbed by this choice and how common it has become even amongst non-commercial backyard beekeepers.

Several years ago, I talked about queens with Horst Kornberger who wrote a wonderful book called Global Hive: Bee Crisis and Compassionate Ecology. We are both concerned about the problems of requeening, which is a practice that modern beekeeping has come to embrace. The existing queen in a hive is killed (or dispatched) and replaced, most often with a virgin or newly mated queen who is often from an entirely different hive of bees (and often from commercial breeders). The new queen is added to a colony that was going along just fine with the queen they had from the bees’ point of view. Many beekeepers are strongly encouraged to requeen their hives every two years and now, even once a year, to ensure (I believe mistakenly) the health, vitality, and productivity of a hive. I am particularly disturbed by this choice and how common it has become even amongst non-commercial backyard beekeepers.

Horst describes honeybees as creatures of connectivity and speaks to the fracturing of the connection between bees and their queen due to requeening, which “tears at the invisible bond in a hive … tears this sacred relationship between the bee community and its queen”. In the natural cycle of things, when a hive perceives its queen is too old, if her pheromones start to decrease or she gets sick, injured or disappears, the colony will choose eggs or very young larvae (from amongst those that the queen herself has laid) as candidates to replace her. Those selected become the future queen contenders and one of them, generally the first born, will emerge as the new La Reina of the hive.

I have never killed a queen bee and never will. I trust a hive to replace their queen, making this kind of important decision for themselves on bee time, exercising bee preference and intelligence. Who of us can really understand the long-deep and long-term effect on a lineage of bees when we frequently requeen? I am distressed by this choice; I feel we are sabotaging the health, resilience, and well-being that come from bees self-determining the succession of their queen.

I feel the practice of requeening also disturbs the innate wisdom of the sacred soundscape and an intergenerational aural continuity that we barely understand as bee stewards. We have been tampering with the bees in this way (and other ways) at a very core essence level for over a century. I believe we are shattering and fracturing the songlines, these very particular and unique vibrations that help create and sustain lineage across time, bonding the queen with the colony, the colony to itself and with the particular place on the web of life they are part of. I believe it is essential that bees select the best eggs for their future queen candidates for all the mysterious reasons they do, for their own divine purpose and destiny. So many of our practices have diminished their input about their future. We’ve become hasty, often putting commercial needs that center on pollination and honey, before the welfare of bees. And we are asking one of the hardest working creatures on earth … to work harder.

Honeybees have long been some of my highest teachers. Between teaching, speaking, and advocating for them on the Good Bee Road and the time I get to spend with them in the bee sanctuary where I live, I feel immersed in a sea of gratitude for their inspiring presence in my life. The most seemingly ordinary moments with these precious wing-ed ones can spontaneously combust into sudden clarity and grace … lifting the veils and dissolving the habitual in favor of a present which is alive and bursting with creativity, a humming sense of purpose, and well-being. When I hear The Song of the Unborn Virgins and other hymns from the hive (as Layne called them), I feel something holy moving through the continent of me … recalibrating me in a profound way and pouring blessings everywhere in my consciousness. For this and so much more, I remain infinitely grateful for my astonishing and astonished life with the bees.

Long live the queens. Blessed be. Blessed bees.

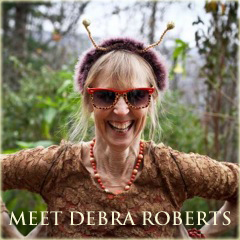

Debra Roberts ©HolyBeePress.com / Thanks to Filiz Telek and Barbara Schacht Randall for photos.

Across fourteen years of being with-bee, some hives have flourished in their many-year’d lineages and others have passed away, returning to some sweet-scented sector of the star nation. In the last five years, those that have left the world have disappeared under more mysterious circumstances, but in the deep-down I know that has to do with human choices that fall somewhere within the spectrum of being more and less asleep.

Across fourteen years of being with-bee, some hives have flourished in their many-year’d lineages and others have passed away, returning to some sweet-scented sector of the star nation. In the last five years, those that have left the world have disappeared under more mysterious circumstances, but in the deep-down I know that has to do with human choices that fall somewhere within the spectrum of being more and less asleep.  Imbolc has just passed. A cross-quarter day, also known as Groundhog Day, tucked in between the winter solstice and spring equinox. The day that Joe and I begin to celebrate spring. More winter lies ahead, but the seeds are stirring in the soil.

Imbolc has just passed. A cross-quarter day, also known as Groundhog Day, tucked in between the winter solstice and spring equinox. The day that Joe and I begin to celebrate spring. More winter lies ahead, but the seeds are stirring in the soil. Amidst the chop wood, carry water seemingly infinite tasks needed to create a new nest, I had even more time with the bees. I discovered other colors of pollen, from pastel to neon, and was astonished to discover that some honeybees exit their hive flying backwards. (How had I never noticed that before?) I laid down in the bee sanctuary, soothed by the smell of new comb and the thrumming humming bee-song soundscape. I read poetry to them (a favorite by Yunus Emre, Come, see what love has done to me) and played them Karsilama and Masmoodi on my frame drum. I shared stories and brought the news … and I emptied my mind to hear theirs. I wept over the death of friends, including bees, and some of the great sorrowing in the world. I marveled as these mistresses of alchemy transmuted the precious nectar of thousands of flowers from the gardens, fields and forest into honey and also wax, the sacred sacraments of the hive.

Amidst the chop wood, carry water seemingly infinite tasks needed to create a new nest, I had even more time with the bees. I discovered other colors of pollen, from pastel to neon, and was astonished to discover that some honeybees exit their hive flying backwards. (How had I never noticed that before?) I laid down in the bee sanctuary, soothed by the smell of new comb and the thrumming humming bee-song soundscape. I read poetry to them (a favorite by Yunus Emre, Come, see what love has done to me) and played them Karsilama and Masmoodi on my frame drum. I shared stories and brought the news … and I emptied my mind to hear theirs. I wept over the death of friends, including bees, and some of the great sorrowing in the world. I marveled as these mistresses of alchemy transmuted the precious nectar of thousands of flowers from the gardens, fields and forest into honey and also wax, the sacred sacraments of the hive. And sometimes, by grace, a singularly illuminating moment would come along … like one fragrant afternoon last summer when a forager landed on my hand. She rested a while, her tiny abdomen heaving from the pollen load, before returning to the colony above us. I wept to know my hand was safe harbor. In that sacred bee time-infused moment, all Otherness dissolved. I felt gloriously undifferentiated from all of life … no veils, no seams, no borders, no edges, no species, no me and non-me, no bee and no beekeeper. Everything was suffused with a deeply tap-rooted, familial and familiar connectedness. In this holy-rolling zone of revelation, presence and love, I remembered my place in the divine matrix of wisdom I share with the honeybees and all life. The intelligence that moves the whole universe of bees along, also moved through me. It was here in the bee sanctuary, beside our burnt then rebuilt home, where I lost my heart and found another bigger one amongst the ripe honeycombs.

And sometimes, by grace, a singularly illuminating moment would come along … like one fragrant afternoon last summer when a forager landed on my hand. She rested a while, her tiny abdomen heaving from the pollen load, before returning to the colony above us. I wept to know my hand was safe harbor. In that sacred bee time-infused moment, all Otherness dissolved. I felt gloriously undifferentiated from all of life … no veils, no seams, no borders, no edges, no species, no me and non-me, no bee and no beekeeper. Everything was suffused with a deeply tap-rooted, familial and familiar connectedness. In this holy-rolling zone of revelation, presence and love, I remembered my place in the divine matrix of wisdom I share with the honeybees and all life. The intelligence that moves the whole universe of bees along, also moved through me. It was here in the bee sanctuary, beside our burnt then rebuilt home, where I lost my heart and found another bigger one amongst the ripe honeycombs. I do not want to save the bees; I want to wake up. I am not asking them to stay; I am deepening my practices and capacity to be conscious and respectful, so they might be persuaded from leaving and thrive in that choice. I remain planted at the feet of the Bee Nation … robust, sentient ambassadors of life who were here millions of years before I was born. A truly venerable first First Nations people.

I do not want to save the bees; I want to wake up. I am not asking them to stay; I am deepening my practices and capacity to be conscious and respectful, so they might be persuaded from leaving and thrive in that choice. I remain planted at the feet of the Bee Nation … robust, sentient ambassadors of life who were here millions of years before I was born. A truly venerable first First Nations people. Joe and I had gone out to enjoy the music of one of our most favorite artists in the world,

Joe and I had gone out to enjoy the music of one of our most favorite artists in the world,  The week before, I had counted eight peanut-shaped queen cells (the birth chambers) in that hive. It takes 15 – 16 days for a queen to be born, to change from an egg to a larva to a pupa and then eventually emerge from her cell as a young adult. She hatches from the bottom of her cell and generally, the first queen born gathers herself, travels to the other queen cells (the ones not yet quite born) and kills those other contenders by stinging them through the wax walls of their birth cells … because only one queen will reign in a hive.

The week before, I had counted eight peanut-shaped queen cells (the birth chambers) in that hive. It takes 15 – 16 days for a queen to be born, to change from an egg to a larva to a pupa and then eventually emerge from her cell as a young adult. She hatches from the bottom of her cell and generally, the first queen born gathers herself, travels to the other queen cells (the ones not yet quite born) and kills those other contenders by stinging them through the wax walls of their birth cells … because only one queen will reign in a hive.

Queen piping also has resonance for me with the concept of songlines, which is something our friend Uncle Bob Randall used to talk about. Uncle Bob was a special teaching uncle and elder of the Yankunytjatjara Nation in Australia. He was one of the great people of our time and a living example of Kanyini, the Aboriginal principle of unconditional love, responsibility, and what he called Oneness with the creative consciousness of the world.

Queen piping also has resonance for me with the concept of songlines, which is something our friend Uncle Bob Randall used to talk about. Uncle Bob was a special teaching uncle and elder of the Yankunytjatjara Nation in Australia. He was one of the great people of our time and a living example of Kanyini, the Aboriginal principle of unconditional love, responsibility, and what he called Oneness with the creative consciousness of the world. It is interesting to note that a queen bee can live three to five years. All the workers and drones, the great numbers of everybody else you see in a colony, only live about six weeks. So there is a big difference in lifespan between a queen and her fellow bees. Where I live in North Carolina, an Italian queen bee (which is the type of bee many of us have in America) can lay almost twenty generations of bees (from eggs to hatched) in the warm weather months of one year. So if you multiply those twenty generations of bees per year times the three to five years of a queen’s life, I imagine a songline that extends its reach to an immense number of bees and beings.

It is interesting to note that a queen bee can live three to five years. All the workers and drones, the great numbers of everybody else you see in a colony, only live about six weeks. So there is a big difference in lifespan between a queen and her fellow bees. Where I live in North Carolina, an Italian queen bee (which is the type of bee many of us have in America) can lay almost twenty generations of bees (from eggs to hatched) in the warm weather months of one year. So if you multiply those twenty generations of bees per year times the three to five years of a queen’s life, I imagine a songline that extends its reach to an immense number of bees and beings. Several years ago, I talked about queens with Horst Kornberger who wrote a wonderful book called Global Hive: Bee Crisis and Compassionate Ecology. We are both concerned about the problems of requeening, which is a practice that modern beekeeping has come to embrace. The existing queen in a hive is killed (or dispatched) and replaced, most often with a virgin or newly mated queen who is often from an entirely different hive of bees (and often from commercial breeders). The new queen is added to a colony that was going along just fine with the queen they had from the bees’ point of view. Many beekeepers are strongly encouraged to requeen their hives every two years and now, even once a year, to ensure (I believe mistakenly) the health, vitality, and productivity of a hive. I am particularly disturbed by this choice and how common it has become even amongst non-commercial backyard beekeepers.

Several years ago, I talked about queens with Horst Kornberger who wrote a wonderful book called Global Hive: Bee Crisis and Compassionate Ecology. We are both concerned about the problems of requeening, which is a practice that modern beekeeping has come to embrace. The existing queen in a hive is killed (or dispatched) and replaced, most often with a virgin or newly mated queen who is often from an entirely different hive of bees (and often from commercial breeders). The new queen is added to a colony that was going along just fine with the queen they had from the bees’ point of view. Many beekeepers are strongly encouraged to requeen their hives every two years and now, even once a year, to ensure (I believe mistakenly) the health, vitality, and productivity of a hive. I am particularly disturbed by this choice and how common it has become even amongst non-commercial backyard beekeepers.